The accelerating pace of technological innovation presents a growing challenge for modern organisations: while tools such as AI, automation, and digital platforms evolve at exponential speed, human systems – culture, leadership, and adaptability – evolve far more slowly. This widening divergence creates what can be called the stress gap – the measurable distance between technological capability and human adaptability.

At the heart of this dynamic lies a paradox: technologies that promise speed and efficiency can, in reality, slow organisations down if cultural readiness, leadership structures, and emotional adaptation are neglected.

Drawing on models such as Kurzweil’s epochs of technological change, Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovations theory, and the S-curve model of technology adoption, this article argues that the success of AI integration depends less on the speed of tool deployment and more on leadership’s ability to foster trust, cultural transformation, and shared meaning.

Human history is marked by profound technological transitions, each dramatically reshaping societies, economies, and ways of life. As technology accelerates, humanity faces a growing challenge: the speed of technological advancement is beginning to outpace our ability to adapt.

This widening gap between the relentless development of tools and the human capacity to integrate and use them effectively is not just a philosophical idea – it directly impacts company culture, tool adoption, employee security, and ultimately the success or failure of organisations.

Ray Kurzweil’s model of technological epochs offers a compelling framework to understand this accelerating dynamic. From agriculture to artificial intelligence, each new era forces humanity to adapt to new realities at increasingly rapid intervals.

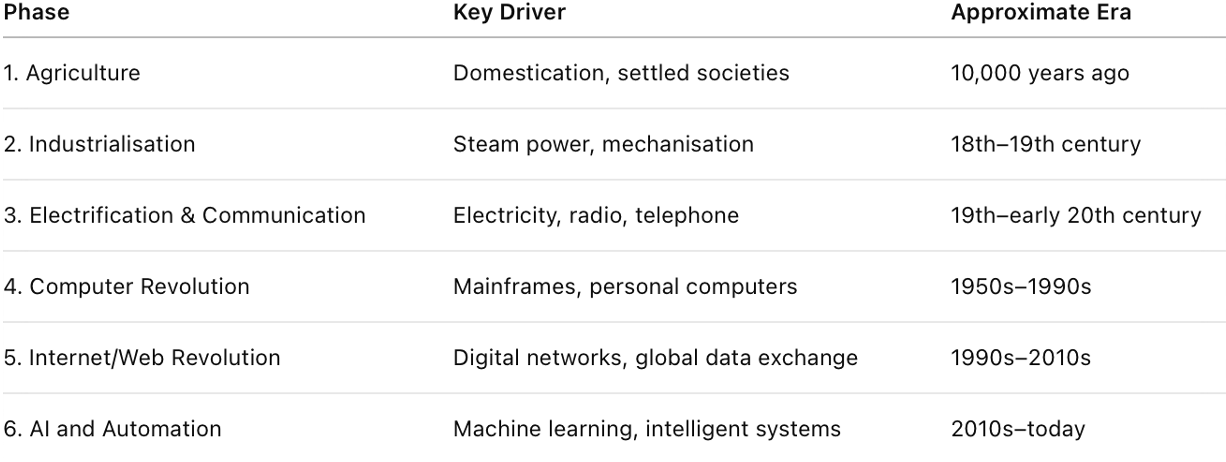

The main technological epochs and their primary drivers can be summarised as follows:

Figure 1: Major epochs of technological development based on Ray Kurzweil’s model of accelerating change. Each new phase compresses time intervals and intensifies societal transformation.

Each of these technological eras not only accelerated change but also followed recognisable patterns in how societies adopted new innovations. Adoption has never been uniform or frictionless.

Everett Rogers‘ Diffusion of Innovations model (Rogers, 2003) shows that new ideas typically spread through specific groups – from innovators to early adopters, then to the early and late majority, and finally to laggards – forming a bell-shaped curve over time.

Similarly, the S-Curve model (Foster, 1986) describes how technologies grow: from slow initial adoption to rapid acceleration, and eventually to a plateau as maturity sets in. Each technological leap follows this S-shaped trajectory, with the steepest phases of growth creating the greatest pressure on individuals, organisations, and societies to adapt. It is in these periods that the widening gap between what technology makes possible and what humans can realistically absorb becomes most visible.

These transitions represented not just a gradual evolution but a disruptive step-change. Following each leap, there was a short phase of slowed progress – a catching of breath – before acceleration resumed and often intensified. With every step, a larger portion of society struggled to keep up, and the pace of technological advancement increasingly outstripped the natural pace of human adaptation.

Throughout history, human development and technological innovation have progressed together – but not at the same speed. At every major technological shift, from agriculture to industrialisation to AI, there has been a sudden disruptive leap: a vertical step-change triggered by new inventions, which forces humanity to adjust. After each step, early adopters quickly integrate the new capabilities, but for the majority, there is a short slowing down – a phase of hesitation, uncertainty, and fear. Gradually, the curve of human adaptation picks up speed again, yet it never quite closes the gap. Technology, meanwhile, continues to accelerate exponentially, unaffected by emotional, cultural, or organisational limitations.

The difference between these two curves – the acceleration of technology versus the slower adaptation of humanity – is the direct origin of stress in modern organisations and societies. Stress is not an abstract or isolated emotional reaction; it is the widening, measurable gap between what tools make possible and what individuals, teams, and entire companies can realistically implement, understand, and master. The larger the gap, the greater the feeling of inadequacy, pressure, and fear. Fear of missing out. Fear of losing relevance. Fear of job loss.

This phenomenon is not new. It can be seen in every major period of change. When the telephone was first introduced in the early 20th century, large parts of society were overwhelmed, unable to comprehend the device’s possibilities or integrate it into daily life. With the rise of the internet and email in the 1990s, another portion of the population was left behind, struggling to engage with a world that had shifted to digital communication. Now, with the arrival of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and Midjourney, the speed of disruption is even faster, and the potential for entire professional groups to feel disoriented or excluded is significantly higher.

As time progresses after each leap, the curve steepens again: innovations become more complex, adoption rates accelerate, and new expectations are created. In this accelerating phase, stress builds – the gap between the capabilities offered by new technology and the human ability to fully adapt, integrate, and govern these capabilities grows wider.

The human adaptability curve follows a similar pattern, but with a slight time delay. After each technological step, humans are forced to catch up – either through education, new cultural norms, or system redesigns – but they rarely match the exponential pace that technology imposes. Each new technological wave thus stretches the gap further, increasing organisational and societal pressure.

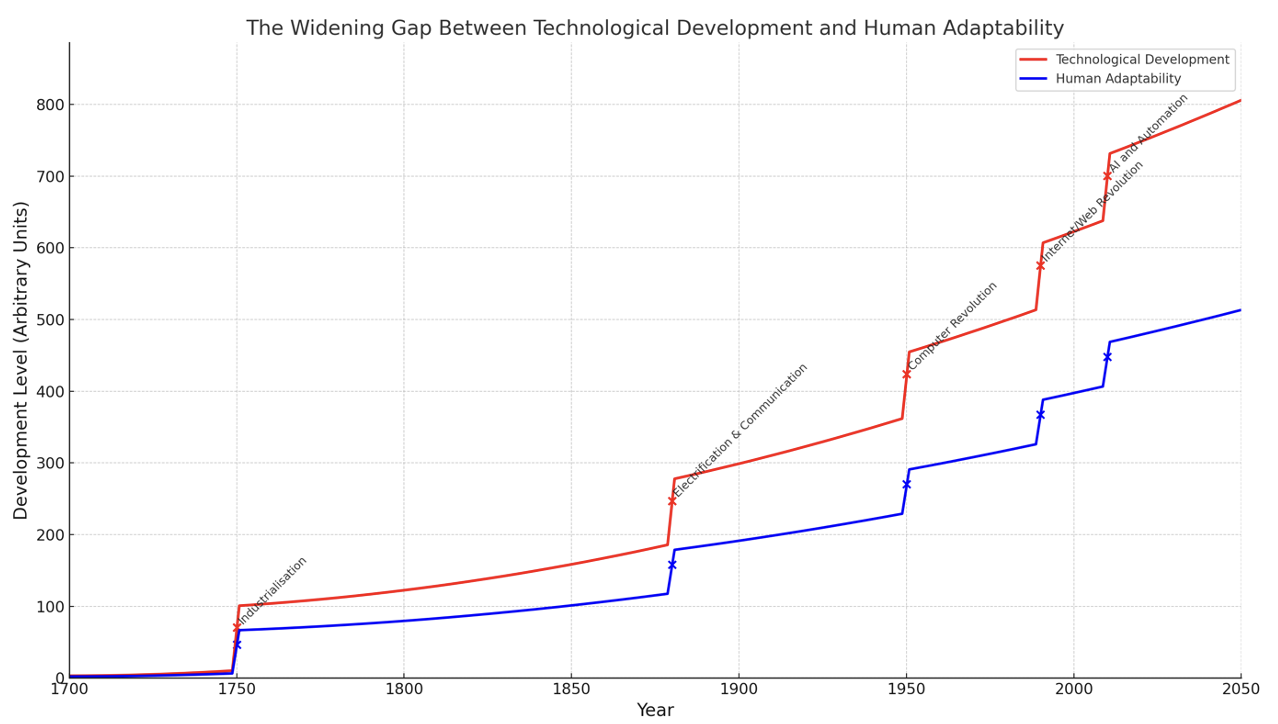

This dynamic – sudden leaps, temporary plateaus, renewed acceleration – shapes the structure of the graph below. The x-axis represents time on a linear scale, starting around the year 1700 with the Industrial Revolution. The y-axis reflects increasing technological capability and human adaptability without compression. The Agricultural Revolution (10,000 BC) is acknowledged as a foundation but lies outside the plotted range.

To visualise this dynamic, we can think of two curves:

- One represents technology’s development – accelerating, with sharp step increases at each epoch.

- The other represents human adaptability – also progressing, but more slowly, and lagging behind each technological leap.

The gap between these two curves is where stress lives: the growing distance translates directly into societal, organisational, and individual anxiety.

Figure 2: The growing gap between technological acceleration and human adaptability, increasing after each major transition.

This pattern can be observed not only in historical terms but also within living memory. At the dawn of the 20th century, many older citizens struggled to adapt to the telephone and electricity. When mainframes were developed in the mid-20th century, they initially triggered a transformation at the corporate and institutional level — much like the steam engine had done during the Industrial Revolution. However, because of their sheer cost and technical complexity, mainframes remained confined to large organisations and had little direct impact on the daily lives of most individuals. It was only with the rise of personal computers in the 1970s and 1980s that a broad societal shift occurred, as digital tools entered homes and offices.

In the 1990s, the emergence of email and the internet created another sharp divide: those unable to adapt were often marginalised from professional life. Today, the advent of AI tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, and autonomous systems marks the sharpest leap yet – and once again, a widening divide opens. At each of these steps, the fraction of society unable to keep pace has grown larger, and the fear of being left behind has deepened.

This is not merely a personal challenge but a corporate and societal one. The introduction of CRM systems (like HubSpot, Salesforce), ERP platforms (SAP, Oracle), project management tools (Asana, ClickUp), communication suites (Teams, Slack), and now AI-driven platforms for automation and content generation is reshaping organisational work structures.

However, technology alone cannot solve underlying human and cultural frictions. A tool unused or misused is no solution at all.

This phenomenon repeats itself in CRM deployments where HubSpot, Salesforce, or Marketo are introduced as „systems“ rather than „ecosystems.“ Employees see them as reporting burdens instead of vital feedback loops that inform smarter decisions. Or in the adoption of productivity tools like ClickUp and Asana, where tasks are entered, but not followed up collaboratively, because the organizational mindset has not shifted from control to transparency and shared ownership.

In practice, new tools require more than installation; they demand cultural adoption. Without a shared understanding of the why and how, many teams fall back into old habits.

This dynamic was evident when proposing AI-driven customer support chatbots in a B2B environment. Despite the clear potential for efficiency and responsiveness, cultural resistance and fear of disruption blocked implementation. The workforce, from customer service to sales, viewed the innovation more as a threat than an opportunity. In the absence of broad communication, leadership sponsorship, and open discussions – such as townhall meetings focused on AI readiness – the technological solution remained largely theoretical.

A similar pattern emerged when introducing AI-driven creative tools like Midjourney. I experienced how the output – ready, powerful, and usable within minutes — was met with scepticism by traditionalists in the team. Rather than embracing the momentum these tools offer, the reaction was: „Next year we could brief an artist to create something like this.“ A complete absurdity – the output was already better, faster, and aligned with the need. Yet the old reflexes of protecting authority, resisting change, and demanding unnecessary preparation created friction that paralysed the organisation. Phrases like „We have no time“ and „Maybe next year“ masked a deeper fear: the loss of control over processes and creative power.

Current tools offer unprecedented opportunities, and acting today positions organisations to shape, rather than be shaped by, the next wave of innovation. ChatGPT, Midjourney, and AI-powered CRM systems already exist to unlock speed, creativity, and strategic advantage. Hesitating today means falling even further behind tomorrow.

China’s rapid embrace of AI and automation creates significant competitive pressure, highlighting the need for greater agility and readiness in European industries. During a recent workshop, a German systems engineer claimed, „The Chinese are merely coping.“ In reality, the situation is very different. Companies like Xiaomi operate fully autonomous gigafactories, and China has launched the world’s first 10G broadband network, enabling unprecedented speed and connectivity (Times of India, 2024).

These developments, combined with national-scale AI deployment, show that China is no longer copying; they are building, scaling, and accelerating beyond traditional Western capabilities. Meanwhile, internal resistance, overcomplication, and fear-driven hesitation in Europe widen our own „stress gaps“ – not just between individuals and tools, but between entire regions of the world.

Friedrich Merz’s recent warning that the EU must „protect itself“ from China copying European ideas shows how dangerously outdated parts of our strategic thinking have become:

„We are facing nothing more and nothing less than a revanchist, anti-liberal axis of states that is openly seeking to compete with liberal democracies,“ Merz said. (Financial Times, 2024)

China is no longer copying; they are building, scaling, and accelerating beyond traditional Western capabilities. Meanwhile, internal resistance, overcomplication, and fear-driven hesitation in Europe widen our own „stress gaps“ – not just between individuals and tools, but between entire regions of the world.

The solution is clear: education, empathetic leadership, cultural transformation, and real empowerment. Tools must be accompanied by trust, transparency, and bold cultural shifts. Otherwise, even the best technology remains trapped inside organisations paralysed by fear of their own future.

Fear plays a central role. Employees are often worried not just about mastering new systems but about losing their jobs entirely. Every major leap leaves parts of society and organisations behind.

The stakes rise with each step. If in the 1990s it was email illiteracy that marginalised some professionals, today it is AI illiteracy that may do the same.

In companies today, success in digital transformation depends less on the speed of new tool adoption and more on the depth of cultural readiness. This includes leadership setting clear expectations, openly addressing fears, investing in training, and most importantly, aligning everyone behind a shared vision of growth rather than elimination.

The paradox of ever-faster tools is this: technology accelerates, but human systems require trust, shared meaning, and emotional security to adapt effectively.

Where there is a lack of transparent communication and collective commitment, even the best tools – from AI co-pilots to fully integrated ERP systems – will fail to deliver their promise.

Understanding the widening gap between the technology curve and the human adaptability curve is therefore not merely an academic exercise.

It is a leadership imperative for every organisation that hopes to thrive in the age of AI and beyond.

We are living not just at the edge of another step-change – we are already inside it. AI, automation, and networked collaboration systems demand faster adaptation than ever before. Recognising the „stress gap“ is the first step toward navigating it.

The winners of the next decade will not be those who adopt the most technology, but those who evolve their cultures fast enough to wield it. The rest will be left behind, not because of a lack of technology, but because of a lack of cultural evolution.

References

Financial Times (2024) German election frontrunner Friedrich Merz warns of ‘great risk’ investing in China. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/65bf800b-545a-42b3-bbd3-64bb1f0f3372 (Accessed: 25 April 2025).

Foster, R. N. (1986) Innovation: The Attacker’s Advantage. New York: Summit Books.

Hawkins, J. (2021) A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence. New York: Basic Books.

Kurzweil, R. (2005) The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York: Viking.

Rogers, E. M. (2003) Diffusion of Innovations. 5th edn. New York: Free Press.

Times of India (2024) World’s first 10G broadband network launched in China: How fast is 10G? Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/technology/tech-news/worlds-first-10g-broadband-network-launched-in-china-how-fast-is-10g/articleshow/120485407.cms (Accessed: 25 April 2025).